The 2024 U.S. Presidential Election and the Potential Impacts on Commercial Real Estate

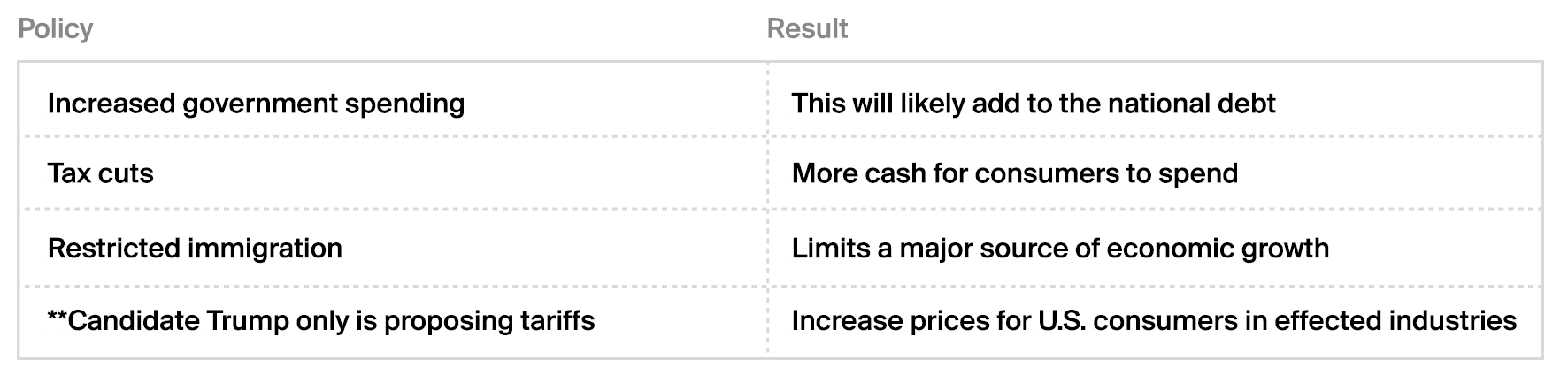

Key Policies and Their Ties to Inflation

Both Presidential candidates’ budget platforms – here Harris and here Trump – outline plans which we anticipate will fuel, or at the least maintain, inflation levels. Below we highlight three shared policies, and one from former President Trump, which we feel could have the greatest impact on CRE during the 2025-2029 term.

The candidates’ proposed policies are expensive and limit federal government revenue generation, which could reverse the efforts to curtail inflation over the last few years.The federal government increased the deficit by $5.9 trillion[1] in 2020 and 2021 through increased spending and tax cuts during the pandemic. According to the Tax Policy Center to fight against unemployment, stimulate the economy, and backstop certain critical industries against the demand erosion from the pandemic[BT1] . Since then, the Fed has done well to bring core and headline inflation to more tolerable levels, but challenges remain, and neither candidate directly addresses inflation management efforts in their policies.

Macroeconomic Indicators

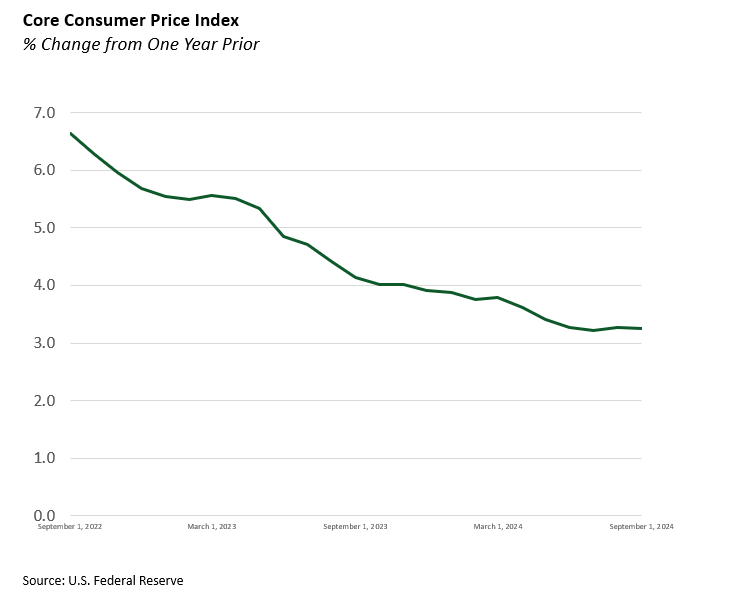

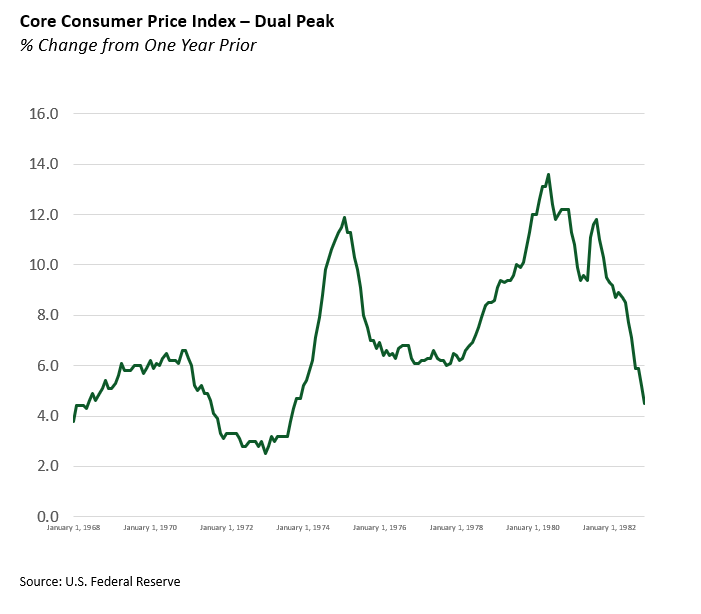

Core Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Core consumer price index (CPI) measurements are beginning to flatten out just above 3%, suggesting it might be more difficult getting that “last mile” to the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target.

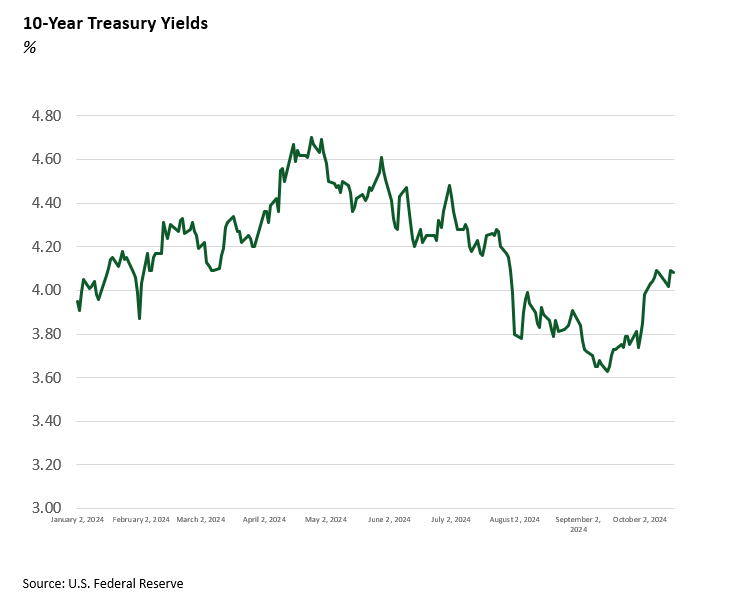

Bond Market

When looking at certain corners of the bond market, like yields on the 10-year Treasuries, we see these have ticked up since the end of the summer. Perhaps the bond market is beginning to price in some recession risk and the prospect of fewer rate cuts going forward. Or maybe it too is looking at the potential fiscal and monetary and fiscal challenges presented by whoever the next President will be. Either way, there is a run up in term premium for 10-year Treasuries that should be worrisome to industries impacted by the cost of debt.

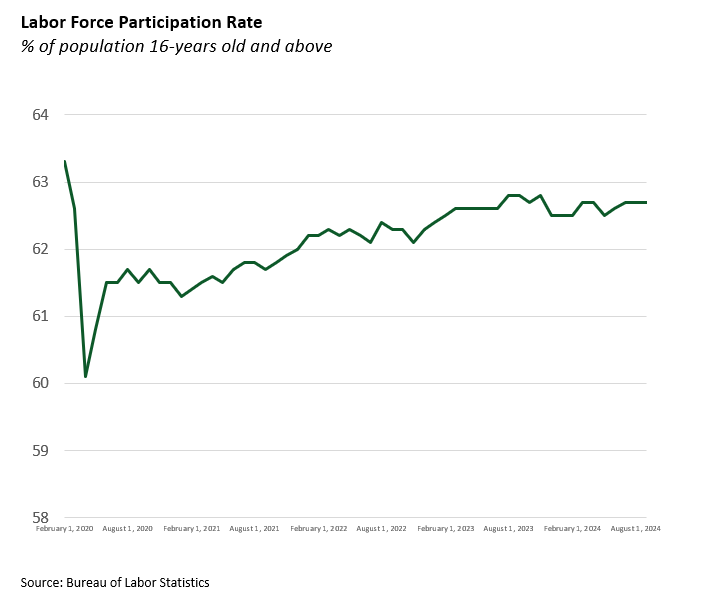

Unemployment

Employment remains healthy, having largely recovered from the challenges of the early pandemic. The U.S. economy has been fortunate thus far to have avoided a “hard landing” following the rapid hiking cycle imposed by the Federal Reserve (and other central banks). This essentially means we have not gone into a recession. The relatively healthy labor market would suggest that the Fed is not in as much of a hurry to aggressively ease monetary conditions. As a matter of fact, the strength of the labor market and stubborn core CPI may tie the Federal Reserve’s hands on any potential future cuts, which if done too early could be inflationary in nature.

International Affairs

Looking at the world beyond U.S. borders, there is an abundance of fodder for any concerned commercial real estate tenant credit pundit. If the conflicts in Ukraine or the Middle East expand, energy prices may begin rising on supply constraints. That alone may not be enough to drive inflation, but if the conflicts draw in new belligerents, conventional wisdom suggests inflation is a natural side effect of war. Additionally, tensions between China and Taiwan, while not directly energy related, could introduce new supply chain strains at a time when governments would be hard pressed to respond without adversely impacting CPI.

Historical Precedents

All the points discussed above have one common thread: inflation. A resurgence of inflationary pressures is possible if regulators and law makers fail to respond effectively. That could spell trouble for rate sensitive industries like real estate, start-ups, software and technology, home building, energy, and other capital-intensive industries.

Historically, there were two peaks in the U.S. consumer price index in the second half of the 1970s and into the early 80s, which were in large part the result of the following forces:[2]

- The energy crisis in the early 1970s imposed by an Arab oil embargo. This was further exacerbated by the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which drove up energy prices

- The U.S. Federal Reserve did not have a written mandate to increase rates until the late 70s

- Supply shocks around food prices drove up prices

- The wage price spiral began to take effect in the middle part of the 1970s

- Enactment of wage-price controls by the Nixon administration, known as the Nixon Shock, which prevented increases in wages and prices for a 90-day period in 1971

The economic impact of some headline policies by both candidates, along with the uncertainty percolating globally, could create similar conditions to drive up prices.

Conclusion

Inflation and the higher interest rates that come along with them tend to penalize high risk companies and businesses reliant on debt to fund capital projects and operations. It also hits the services sector as consumers become more stretched to find disposable income as wage growth tends to lag inflation. Of course it’s worth noting that candidates say a lot on the campaign trail, and much of what they say is not enacted as they outline prior to taking their seat in office. The reality may vary from what see outlined by both candidates.

For TRA’s clients, it means that looking at their commercial mortgages and being aware that interest rates may not be coming down as much as we initially thought when the election cycle began late last year. It may also signal potential pain for tenants across sectors, including retail, life science, technology, real estate, private equity, all of which are rate sensitive industries that may not have underwritten a potential second round of inflation.

[1] https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c11462/c11462.pdf

[2] https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-deficit/

Download File